Baghdad, a joyful land for the affluent, For the destitute, an abode of anguish and sorrow.

The geographer Yaqut al-Hamawi (d. 1229) says that when the second Caliph of the Abbasid family Abu Ja'far al-Mansur (d.775) decided to build a new seat for the Caliphate, a place called Baghdad attracted his attention. It was a vibrant thriving trading center or suq to which goods and provisions were brought from the four corners of the world by land, river, and sea, as far east as India and China. Although it was referred to as qarya ‘village,’ it seemed to have been teeming with life. He also quotes some of Ptolemy’s (d. c. 168) topographical facts on Baghdad. The name Baghdad was said to be of non-Arabic origin and stories differ on its meaning.

Some say, for instance, it was composed of bagh ‘orchard’ and dad ‘gave. One of the Arabic names chosen for the city was Dar al-Salam ‘the abode of peace. Rapidly the city grew economically, culturally, and intellectually. It was described as um al-dunya ‘mother of the world,’ and surrat al-bilad ‘navel of the nations.’ The only snag, though, one needed to have money in one’s pockets to enjoy its promised luxuries.

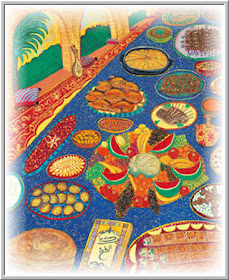

The rapid growth of Baghdad during the Abbasid dynasty created prosperous leisurely classes that demanded the best wealth could offer, which naturally included gourmet cuisine. Indulging in luxuriously prepared foods, cooking, reading and writing about food in prose and poetry, and even arranging for cooking contests—as Caliph al-Maamun used to do— were commendable pastimes that the ruling dynasties and the affluent enjoyed, sometimes to fault.

Al-Wathiq (d. 847), grandson of Harun al-Rachid, was known for his weakness towards food, especially eggplant. He was known as al-Akul ‘the glutton.’ He used to eat forty cooked eggplants in a single sitting. Expectedly, obesity, one of the inevitable ‘side effects’ of gormandize was to be tackled. An anecdote has it that Harun al-Rashid’s paternal cousin Isa bin Ja'far (d. c. 800) accumulated so much fat that Harun al-Rashid was terribly worried about him. The physician’s verdict was that that was due to self-indulgence and easy living, and he managed to cure him with a lie. He told him that he needed to write his will for he was afflicted with an incurable disease and might die within forty days. Grief-stricken b^s§ lost so much weight that he was able to cinch his belt five notches tighter. Ibn Dihqana (d. 891) was a gourmet and author of a cookbook. He was described as large and overweight. When a Caliph would leave the assembly and come back, the boon companions would stand up but he would fall asleep saying this was because he could not do so. He used to say, “I ate until I got afflicted with chronic diseases. Now I want to eat until I die.”

As for the depressed, food was their solace and diversion such as in the case of the unfortunate Caliph al-Mustakfi (d. 949). His boon companions, at his suggestion, recited gastronomic poems after which the dishes described were cooked and enjoyed. The narrator in al-Mas'ud's’s Muruj al-Dhahab comments,

'Never have I seen Mustakfi so overjoyed, since the day of his accession. To all present, revelers, singers, and musicians, he gave money, causing all the silver and gold with which he stood possessed to be brought out of the treasury, in spite of his straitened circumstances. Never a day like this did I behold, until the day when Ahmad ibn Buwaih the Dailamite seized him and put out his eyes'. (Arberry 29-30)

Flights of extravagance were not always allowed to pass uncriticized. A case in point is the famous platter of delicate and delectable qans, aspic dish of fish tongues—150 of them—which Ibn al-Mahdi offered to his half brother Harun al-Rashid. Al-Rashid chided him, for no dish, he told him, was worth such outrageous expenses. It went down in history as “the fish dish that cost one thousand dirhams.” Food was also a means to butter one’s ladder up to the top. Al-Warraq, for instance, gives a recipe for kardanaj chicken (grilled on a rotating spit), which an official sent as a gift to his superior, governor Mu'nis al-Muzaffar (d. 933), on a hot summer day. The dish must have made such a positive impression on al-Muzaffar that it was immortalized in cookbooks. Food was a means of expressing one’s affection towards loved ones. Al-Amun sent a basket of cookies to his uncle, Ibn al-Mahdi, who returned the favor with a poem in his praise. Delicious food can save one’s neck at times. When Caliph al-Muhtadi (d. 870) came to power, he got rid of his predecessor’s men but spared Abu Nuh al-Katib, secretary and vizier. His justification was that Abu Nuh’s mother used to send him presents of kamakh ‘fermented condiment’ as delicious as nougat natif ma'qud, and olives as big as eggs.

Medieval Muslims regarded food not only as a legitimate source of pleasure but also a means for physical regeneration —preventing and curing illnesses. Therefore, there was a great demand for physicians’ dietetic guides and cookbooks on islah al-al'tima ‘remedying foods,’ such as Manafi al-Aghùdiya wa Daf Madarriha (benefits of food and avoiding its harms) by al-Razi (d. 923) and the books of the Nestorian physician, Ibn Masawayh (d. 857).

This might explain al-Warraq’s dedication of a good number of chapters to this aspect of food. It was known of Harun al-Rachid and his successors that they had their meals under the watchful eyes of the famous physician Yuhanna bin Masawayh. He would advice them against certain foods and if they did not heed the advice, he would treat them to avert their harm. Al-Mubta'id (d. 902) had his most trusted confidant, Ibn al-Tayyib al-Sarakhsi (d. 899) the eminent scholar, write for him Kitab al-Tabikh ‘cookbook,’ divided according to the days and months of the year.

Proficiency in the art of cooking was therefore a common pursuit in which the public participated alongside professional chefs. It was one of the desirable accomplishments of the ‘Abbasid man,’ especially the aspiring boon companion, who wished to win the favors of his superiors. A cookbook in the mix would definitely be a bonus in his credentials. This also gave rise to a genre of books that dealt with the etiquette adab of dining and wining with one’s superiors such as Adab al-Nadim by Kushajim. The perfect nadÊm ‘boon companion, for instance, was expected to perfect at least 10 exotic dishes.

A number of the Abbasid Caliphs and princes themselves were known for their interest in cooking. Some did it as a recreational activity, of course, but Caliphs al-Ma'mun and al-Mu'tasim, sons of Harun al-Rachid, sponsored cooking contests and participated in some of them. The most passionate about cooking among the Abbasids was Prince Ibrahim bin al-Mahdi, half brother of Harun al-Rachid. His cookbook enjoyed wide circulation in the medieval Islamic world. Indeed, his culinary skills did prove handy when he had to cook for himself during his fugitive days after his nephew al-Maamun claimed the caliphate.93 Stressing the importance of food hygiene, the anonymous writer of the thirteenth-century Andalusian cookbook, Anwa'al-Saydala says that many Caliphs and kings had their food cooked under their supervision, and some, driven by necessity, cooked it themselves .

These contemporary sources testify that what is extant today is the mere tip of the iceberg of the medieval culinary tradition that flourished hand in hand with the papermaking businesses. Material prosperity during the Abbasid era created a social class, the nouveau riche, whose desire to emulate the aristocracy might have also played a role in the popularity of cookbooks. They had the means but lacked the knowledge. Cookbooks such as the one al-Warraq compiled would expectedly be in demand as they described the fashionable favorite dishes the elite enjoyed, which can be duplicated in their own kitchens. Perhaps al-Warraq’s commissioner was one of them. As for the general cooking manuals, they were mostly written for the use of the stewards of “the urban bourgeoisie,” who had to meet the demands of big households, as well as the “customary obligations of providing hospitality” to guests.

Professionally, cookbooks and apprenticeships were used to prepare cooks in the culinary arts. Abu Hamid al-Ghazali (d. 1111), for instance, in his section on bakers, cooks, and butchers, recommends that cooks consult Kushajim’s cookbooks if they want to learn good cooking (Sirr al-'Alamayn).

Needless to say, contrary to the haute cuisine of the affluent ta'am al-khassa, cooking of the masses t'am al-'amma was largely an oral tradition, worthy of being documented only when given elaborate lofty touches. A case in point is the thand dish. It can be as simple and cheap as bread sopped in fava beans or chickpeas broth, with or without meat, or as laborious and costly as the meat preparations we encounter in al-Warraq’s, where more expensive cuts of meat are used, a wider variety of spices is added, and artistic garnishes and presentations are required. However, we can safely assume that the commoners al-'amma did enjoy good food, in normal circumstances at least. The trendy dishes the affluent enjoyed such as the varieties of stews called sikbajat and zirbajat were also popular among the rest of the community.

This we learn from an anecdote al-Mas'udi tells on the Abbasid Caliph al-Mutawakkil (d. 861). He was once sitting at a place overlooking the Gulf, and happened to smell sikbaja stew being prepared by one of the sailors on board of a ship. He liked the aroma so much that he ordered the pot to be brought to him. The pot was returned to the sailor, filled with money, with a message that the Caliph appreciated his food. Later on, whenever the subject was brought up in his assemblies, he would say it was the most delicious sikbaja he had ever eaten (al-Mas'udi 581).

The less privileged classes would definitely confine themselves to what was readily available in the markets such as seasonal vegetables and pulses and cheaper cuts of meat. Spices were added sparingly, and sugar syrup rather than honey was more commonly used for desserts. Purchasing ready-cooked foods from the markets ta'am al-suq was sometimes even more affordable than cooking at home, due to fuel costs. This might explain why it was not deemed fit for high-class people to patronize such places. Caliph al-Ma'mun (d. 813) once went incognito with friends to a cookshop specialized in serving judhaba.

When he was reminded that the dish was ta'am al-'amma ‘food for commoners,’ he said, “The commoners drink cold water like we do. Should we abandon it for them?” Generally, cooked foods available in the markets were regarded as inferior in quality to homemade varieties, even though they looked more tempting. An attractive but deceitful person was usually compared to falùdhaj al-suq. All the same, ready-cooked foods were acceptable options to feed surprise guests. Describing a dish of market-roasted meat shiwa'suqi, a poet says,

'When unexpectedly at dinner time a guest came by, I bought him meat, sweet and tender, roasted by son of a bee'.

It goes without saying that it was the commoners who suffered most in times of hardships. The medieval historian, al-Dhahabi, movingly describes how during the famine of Baghdad in the year 944, women went out into the streets in groups of tens or twenties crying out, al-ju! al-ju! (hunger hunger) and fell to the ground one after the other and died. The Abbasid Baghdadi Cuisine as Manifested in Kitab al-Tabikh. The key to good cooking was freshness of ingredients and hygiene. Al-Warraq made a point of emphasizing this early on in his book. He asserted that what elevated a dish to the high cuisine status was not the expensive ingredients as much as the utmost care taken to clean the food and the receptacles and tools used in handling it. Al-Warraq, in this respect, valued a keen sense of smell. Put a stone in one nostril, he instructed, and smell the washed pot with the other. If they smell the same, the pot passes the test.

Ingredients needed to be handled carefully, particularly meat. Knives and boards for cutting meat were not to be used with vegetables. Otherwise, the cooked dish would acquire an unpleasant greasy odor, called zuhuma, a dire stigma in a dish. For the same purpose, the froth raghwa of the boiling meat had to be skimmed. In fact, in some of the recipes in which the broth was required to stay clean, clear, and free of any particles such as in ma'wa milh (meat cooked in water and salt, the meat was given an initial brief boil after which it was washed in cold water, wiped, and cooked again.

Such attention to detail was necessary in the demanding cuisine al-Warraq describes. In his second chapter on implements and kitchen tools, for example, he gave an extensive list of utensils, including several stirring spoons and ladles because a variety of foods were expected to cook simultaneously. The pestle and mortar used for pounding meat, vegetables, and other ingredients that contain moisture were made of stone. Dry ingredients such as spices, sugar, and salt were pounded in brass mortar. Natif ‘nougat’ was cooked in a rounded pot with three legs to prevent the pot from revolving while beating and whitening the candy away from the fire.

As al-Warraq stipulated, the kitchen stove mustawqad was to be large enough to accommodate more than one pot. Smaller rounded stoves were needed to cook desserts such as falùdhaj and khabis‘condensed puddings.’ Within the course of the recipes in the book, other cooking implements were mentioned such as a trivet called daykadan. It was a handy device used to support pots, which needed to be raised above the fire. It was also put above the smoldering coals of the tannur to allow the pots to simmer slowly.

The small portable stove kanun ‘brazier’ was also used, especially on picnics. A porridge dish called hansa kanuniyya was eaten at the same place where it was cooked. Other portable stoves al-Warraq mentioned were nafikh nafsihi and kanun 'ajlan. The first literally means ‘a stove which blows its fire by itself,’ i.e. it does not need someone to blow it to keep it going. It seems to have been a relatively familiar gadget in the affluent kitchens of medieval times.

It was a slow-burning stove that allowed delicate pots like those made of glass and delicate foods like green stew to keep on cooking over a prolonged time. Kanun 'ajlan was another type of slow-burning brazier. It might have been called 'ajlan either because it was made of clay, which, compared with metal, would allow for slow cooking. In this case, the name derives from bajal ‘clay.’ There is also the possibility that the name derives from bijla ‘bottle of oil’ (Steingass). In this case, we may assume that fuel used for this stove was zayt al-waqud fuel oil, which ignites much faster than coal, and hence the name kanun 'ajlan ‘a brazier that ignites quickly. On such stoves, most of the Abbasid dishes were cooked and the fuel used was mostly firewood and coal. When firewood was used, the non-smoking varieties were preferred. Otherwise smoke would be blown back to the pot and spoil its flavor. Food was cooked in different degrees of heat. High heat required waqÊd ê9adÊd; medium heat, waqid mu'tadil; and low heat, waqid layyin. A strong fire was described as having tongues. When the stew got to the last stage, the directions were to stop fueling the fire to allow the food to simmer gently and the fat to separate and rise to the surface.106 Such directions as removing the fire and letting the pot settle in the remaining heat indicated that the fuel was put in moveable containers.To keep the food clean while cooking and prevent flies from falling into it after it has been cooked, the pots were kept covered with their own lids and the serving bowls were carried to the table covered, too.

Such a demanding and ambitious cuisine prompted the Abbasid cooks to be inventive in devising their own implements and techniques. A water-bath pot was called for to cook a delicate cake batter high in egg content. It was made by taking a big pot, and arranging in its bottom some cane leaves. The cake pan was put inside it, and water was poured in the big pot. A low-heat fire was started underneath the big pot so that it boiled gently with its tight lid on. When slow cooking was required, as in preparing ma al-shdir ‘barley broth,’ a double boiler was devised by putting the pot with crushed barley and water in another pot that had water in it. To prepare simulated bone marrow mukh muzawwar, spleen and sheep’s tail fat were pounded and stuffed in a leaden tube then boiled in liquid. When taken out of the tube, it would look cylindrical like bone marrow. Another way for doing it was to pound shelled and skinned walnut, and mix it with egg white. The mix was put in a cup made of glass and then placed in a pot, which had water in it. Thus, the mix would cook in hot water bath.

Another inventive device was a steam cooker to prepare dakibriyan, which al-Warraq defines as shawi al-qidr ‘pot-roasting’. A rack was made by piercing six holes around a high-sided soapstone pot, half way between the top of the pot and its bottom. Three trimmed sticks of willow wood khilaf were inserted through the holes, long enough to stick out of the pot. The holes were sealed from the outside of the pot with dough. Then water was poured to the level just below the sticks. A fatty side of lamb was sprinkled with salt, rubbed with olive oil, and put on the arranged sticks. The pot was then covered, sealed tightly with mud, and put on the fire to cook. Of the most popular dishes cooked on stoves, meat stews loomed large. Lamb, kid’s meat, beef, and poultry were used.108 There was a great variety of such dishes in al-Warraq’s cookbook, some plain, some sour, and others sweet and sour. Water was added to the pot, with meat and fat, and was skimmed as needed. Within the course of the cooking, other ingredients would be added such as vegetables, spices, herbs, and thickening, sweetening, and souring agents. Of these, spices and herbs—collectively called abazir—were the most essential ingredients, attentively incorporated into dishes, with an eye on balance and fine taste. When everything was cooked, fuel was cut from underneath the pot, which allowed the pot to simmer gently in the remaining heat. The general instruction was to leave it in this state for an hour sa'a, which need not be taken literally. A telling sign that the stew was ready to serve, was when the pot’s oils and fats separated and rose up to the surface. This indeed might take a good while. The stews were usually served hot as the principal component of the medieval meal. They were eaten with bread, or prepared tharid way. Broken pieces of bread were sopped in the broth and the cooked meat was arranged all over the tharid bowl or around the sopped bread. They preferred to arrange the tharid dishes pyramided musa'nab. The ancient tannur was at the center of the baking scene.

In the second chapter al-Warraq gives features of qualifications of the well built tannur and where best to put it. It was used for baking bread and cookies, and slow simmering of pots and casseroles, called tannuriyyat, like porridges, bean dishes, potpies, and heads and trotters. It was also used to roast meat such as a fatty whole lamb or kid—mostly stuffed, spiced whole sides janb mubazzar, big chunks of meat, plump poultry, and fish. They were placed on flat brick tiles arranged on the fire, or securely threaded into skewers and lowered into tannur so that they roast to succulence. When lean or not-so-tender pieces of meat were used, marinating or parboiling was resorted to. A pot with some water was put underneath the roasting meat to receive the dripping juices and fat. Roasting in the tannur was usually referred to as shawi, and the roasted meat is shiwa. A sumptuous casserole-like dish, called judhaba, was baked in the tannur. It was a sweet preparation, which looked like a bread pudding, layered in a casserole, called judhabadan. It was placed inside a slow-burning tannur with meat suspended above it. It might be a fatty side of lamb, a plump chicken, or a duck. As the suspended meat slowly roasted, fats and juices would drip into the casserole, resulting in a sweet and salty luscious dish. The basic recipe for the pudding was composed of pieces of white bread sopped in water until they puffed then spread in the pan and drenched in sugar and honey.

In some of the recipes, sheets of ruqaq ’large and thin bread were layered with pieces of fruit such as banana, melon, mulberry, or crushed raisins and then drenched in sugar. To serve the dish, the casserole was inverted onto a platter. No similar clear instructions were given in the recipes regarding the accompanying grilled meat—probably too obvious to mention. One of the ninth-century stories in Maqamat of Badi al-Zaman al-Hamadani tells us that the meat was thinly shaved and served with the bread pudding. Judhaba was one of the popular dishes purchased from the food markets.

People used to send some of the dishes they prepared at home to the commercial big tannur when more controlled heat or prolonged simmering or roasting was required. For instance, al-Warraq recommended baking basisa ‘crumbled pie’ in tannur khabbaz al-Rusafi, which might have been a famous bakery in the eastern side of Baghdad. A whole stuffed kid was to be sent to tannur al-rawwas, which was the tannur of venders specialized in serving the popular simmered heads and trotters of cows and sheep. The pots were kept in slow-burning tannur overnight to be ready for customers early in the morning.

Another way of preparing meat, and sometimes vegetables like truffles, was grilling them as kabab. The meat was cut into pieces, skewered, and grilled on open fire. It was sometimes pan-grilled. Mukabbab designated meat or vegetables prepared this way. This was the most basic and perhaps the most ancient technique of cooking meat. A more ‘advanced’ grilling method was kardanaj ‘grilling on a rotating spit’ mostly used with plump chicken and pullets. A feather was used to baste the revolving chicken with oil or other ingredients such as spices and murri (liquid fermented sauce, Chapter 90). It was eaten with dipping sauces sibagh and bread.

No food symbolized the leisurely Abbasid urban cuisine more than ruqaq bread, large and paper-thin. An anecdote tells how a Bedouin in the city mistook the sheets of bread for fabric.It was usually baked on tabaq, which was a slab of fired-brick or a sheet of metal. However, we learn from al-Warraq’s recipe that they were also baked in the tannur, one at a time.

The commercial bakery furn was the place to go to for a variety of bread called khubz al-furn ‘brick oven bread.’ It was crusty and pithy bread, thick and domed. The commercial furn had a flat floor. Fire was lit on one side and the shaped breads were transferred with a peel and put on its hot floor. Another design had a slanting brick wall with pebbles on it. The fire was lit in front of the wall and the shaped breads were put on the hot pebbles. Some people preferred to make the dough themselves and have it baked there for a fee, which could be a portion of their dough. Because heat in these ovens was more controlled, some pastries were prepared at home and then sent to bake in the furn. One of the options al-Warraq gives in a recipe for a delicate crumbly pie was to bake it in a furn.

Using malla to grill meat was a perfectly acceptable option for high cuisine regardless of its humble Arab-Bedouin origin. Meat cooked this way was called mallin. One of the delicious methods for preparing truffles was mamlul. Cut-up truffles or whole unpeeled ones were buried in the hot ashes of malla. The first variety was sprinkled with coarse salt and eaten hot. The whole ones were peeled then slightly mashed with salt and pepper.

Preliminary courses offered before the hot substantial dishes included an array of appetizers collectively called udm (sing. idam) such as seasoned coarse salt milh mutayyab, condiments like kawamikh and bin ‘fermented dips’, pickles, fresh herbs, and so on. They were usually served with bread. Cold bawarid dishes of meat and vegetables were served with their appropriate dipping sauces sibag to help with their digestion. The sauces were sour-based and often thickened with ground nuts. In the Abbasid popular culture, the cold dishes bawarid were nicknamed baraid al-khayr ‘harbingers of good news. Dainty sandwiches, called bazmaward and awsat, were also offered, as well as filled pastries of sanbusaj, various kinds of sausages laqaniq, and yogurt dishes like jajaq. Fresh and tender herbs, called buqul al-ma'ida ‘table vegetables,’ such as table leeks, rue, mint, tarragon, thyme, and basil, were used as garnish and appetizers. They were described as ‘ornament of the table.’ However, hearty eaters

In 'Annals of the Caliphs’Kitchens'- Ibn Sayyar al-Warraq’s Tenth-Century Baghdadi Cookbook - English Translation with Introduction and Glossary By Nawal Nasrallah, Brill, Leiden (The Netherlands) & Boston (U.S.A), 2007, (Arabic text edited by Kaj Öhrnberg and Sahban Mroueh -The Finnish Oriental Society, Helsinki, 1987) p,29-35. Digitized, adapted and illustrated to be posted by Leopoldo Costa.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Thanks for your comments...