3.28.2016

THE ASSYRIAN ECONOMY

The economic structure of Assyria was considerably transformed by the evolution of the state into an imperial power; it will be the aim of this section not only to analyse the structure which evolved but also to highlight features of it which are relevant to the fall of the empire. Given that the economic system was gradually altered, it is necessary to consider separately the economy in the two areas, the Assyrian heartland and the empire. In Assyria proper the economic base was agriculture, animal husbandry, and trade. All three of these activities were practised from ancient times, since they were natural pursuits in an area with the geographic features of the Assyrian heartland.

The southern border of this area, where the city state of Ashur was located, coincided with the southern limit of dependable annual rainfall, so that Assyria's meadows could be cultivated with considerably more ease and profit than those farther south in Babylonia, where artificial irrigation was vital. The position of the city of Ashur, at the point where the Jebel Hamrin fades into the Jezirah, was also significant for trade, since it was a strategic point for crossing the Tigris on the east—west trade route as well as being on the north-south route along the Tigris. The inhabitants of the Assyrian heartland were compelled to trade from earliest times because, apart from the produce of their fertile land and some stone for building in the north, the area had no natural resources. This statement seems ludicrous today, since one of the world's great oilfields is located on the very edge of the ancient Assyrian heartland.

The main cereal grown was barley although other grains, such as wheat and emmer, were known. Barley was used for bread, sesame was grown for oil, and flax for linen. While the beer brewed from barley was the staple drink, vineyards produced wine, the supply of which was augmented from immediately adjacent areas in the mountains. Orchards and gardens yielded fruit, nuts, leeks, onions, and cress. The most common animals bred were cattle, sheep, goats, donkeys, mules, and various kinds of fowl such as ducks. The fowls produced eggs, the goats provided milk, with its by-products of butter and cheese, and the sheep were raised for wool. Cattle, donkeys, and mules were used as draught animals and beasts of burden. On special occasions an animal was slaughtered for its meat and hide. The shepherd worked on a contract basis, whereby he paid the owner a fixed portion of the flock's yield and kept the remainder. In the Neo-Assyrian period all animals were subject to a state tax.

In theory all land belonged to the god, represented by the crown, while in practice the state owned only a certain portion, the remainder being held by the temples, wealthy families, and private individuals. In addition to outright private possession, land could be held under an arrangement called ilku. By this method, the client had the use of the land in return for performing state service, both civil (road building, canal repairs, and so on) and military. It should be noted that a few scholars believe the ilku was not associated with land tenure but simply with the fact of being an Assyrian; however, most believe that originally the ilku was applicable only to land-holding and by Neo-Assyrian times the proportion of the population not working on the land had increased to such a point that it was necessary to impose ilku on citizens throughout the state. The more important and wealthy were allowed to make payments in lieu of service, and in the case of large estates where ilku was involved the owner was expected to produce a certain number of men for ilku and would not himself perform the service. The absence of an ilku obligation on a piece of land was an asset and was duly noted in sale documents. It is unknown what proportion of the entire land area of the state was held under ilku, but all cultivated areas, whether subject to ilku or not, were assessed a grain and straw tax.

As for trade, because of lack of natural resources the list of imports was extensive and included metals, timber, precious stones, ivory, horses, camels, wine, aromatics, and possibly silk from China. The principal export was manufactured goods, particularly textiles, but of equal importance with the export of goods was the fact that Assyria was a crossroads for major trade routes, including those to and from Babylonia and the Persian Gulf. In practice trade was conducted not by the Assyrians themselves but by Aramaeans, Phoenicians, and Arabs, to name some, and this fact accounts for the lack of cuneiform documentation on trade. The state reaped profits from the trade through the imposition of customs duties (quay tax, gate tax, and so on) and through the indirect benefits of a thriving economy.

Crafts in Assyria were conducted in the palace and possibly also in the temples and large estates. Before Neo-Assyrian times the crown issued raw materials to the craftsmen and they returned all finished products to the crown, their subsistence being provided extra. But in Neo-Assyrian times the craftsmen worked on a contract basis, whereby they repaid the crown for the raw materials in other forms, not necessarily in manufactured goods, and kept a certain portion of the raw materials as commission.

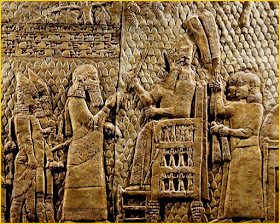

Going beyond the confines of Assyria proper, the economy of the areas ruled varied according to local conditions, but the empire profited from each and every one of them by the receipt of tax and tribute. Taxes were imposed upon the provinces proper, while tribute was collected from the regimes which were under obligation to Assyria by treaty. Both taxes and tribute were rendered in kind and included exotic imports as well as the animals which were used to support local administration and armies. Tribute was paid annually at an appointed time, when the representatives of each government paraded before the Assyrian king with their contributions borne in state. On this occasion the Assyrians required the ambassadors to renew their treaty oaths (adu) on behalf of their rulers. Bulky items, such as grain and animals, were delivered to an Assyrian centre close by rather than being brought to the capital.

Tribute came under the direct jurisdiction of the crown, regardless of where it was deposited, while taxes in the provinces were collected by the local governor and his bureaucracy. The ilku and the grain and straw taxes mentioned earlier also applied to the provinces but, of course, not to the vassal states. In addition, in the provinces there were agents (musarkisu) directly responsible to the king who gathered horses and raised levies of troops for the royal armies. The booty taken on foreign campaigns consisted of luxury items and became the property of the palace to dispose of at will. Some was kept but some was distributed to the temples, to provincial governors, and to the nobility.

The leading economic institution in the state was the palace, but it did not have a monopoly, for industry and commerce were conducted by the large estates and by smaller units and individuals. The temples still had independent revenues from their land, but the increase in their size in the Neo-Assyrian period had made them dependent upon royal favour in the form of transferred taxes, ilku, and a portion of the booty, in order to survive economically. It was possible, as noted in Section II above, for a man and his family slowly to build a fortune by acquiring land and its revenue through skilful management and clever transactions.

The standard of exchange in business deals was silver or copper, both being used contemporaneously, but copper being more common in the eighth century and silver in the seventh century. The metal was only a standard and did not actually change hands except in the few instances where it was the substance involved. This is in contrast to Babylonia in a later period, where regular statements about the form and quality of the metal indicate that it did change hands. There is no clear evidence that coinage was used in Assyria. Of equal importance with a standard of exchange was a standard of weights and measures, and it is commonly stated in the documentation which standard was being followed, both the 'mina of Carchemish' and the 'royal mina' being in common use. Official weights, of stone or metal in the shape of ducks or lions and with a cuneiform label indicating weight and royal name (where applicable), were available for checking and some of these have been recovered in modern times. A careful account was kept of business transactions and hundreds of administrative tablets, mainly from palaces, have been recovered. The main types of documents represented are debenture lists, credit lists, inventories, accounts, tax assessments, census lists, and notes and memoranda of all kinds.

Prices fluctuated according to supply and demand, and there is no suggestion that the state ever fixed or controlled prices. A fitting illustration of this is Ashurbanipal's boast that he brought back so many camels from his Arabian campaigns that the price of camels in Assyria plummeted to a ridiculously small sum. Given the nature of our sources, we cannot assess the standard of living in the Assyrian empire, although it is clear that it would have fluctuated with the fortunes of the state as a whole, and there is every indication that the upper classes enjoyed many exotic luxuries during the great days of Assyrian power. It is equally apparent that in such a highly centralized system the outlying regions of the empire were relatively economically depressed areas.

This last observation leads to some concluding remarks on the problems and weaknesses in the Assyrian economy. The concentration of supplies and wealth in the large cities gave great strength and authority to the crown, a necessary adjunct to a political structure based on royal absolutism, but, as Postgate has pointed out, it meant that Assyria was vulnerable to disruptions of supplies from its outlying regions and these regions were, in addition, deprived of their internal viability and strength. Garelli has suggested that there is evidence of increasing inflation with the devaluation of silver brought about by the large quantities of that precious substance flowing into Assyria.

Another problem was the continual increase in the number of people not directly engaged in food production, members of the state bureaucracy and most of the urban dwellers. As early as the reign of Tiglath-pileser I (1114-1076 B.C) Assyrian kings were expanding the area of land under cultivation and forcibly transporting peoples to work on it, in order to supply food for this growing segment of the population. Such a process could not go on indefinitely.

While the expansion of the Assyrian empire in its initial phases stimulated the economy by bringing a great deal of wealth and manpower under the sway of the Assyrian state, the stimulus could not have permanent effects without some major readjustments to the economic structure. Conquered regions could produce only so much, even with the best will in the world, and the inhabitants of these areas were naturally reluctant to work hard only to see the greater portion of the fruits of their labours carted off to a foreign country. They were hesitant to engage vigorously in foreign trade under Assyrian eyes since the more wealthy they became the more attractive their assets were to Assyria's covetous eyes. The Assyrian state's only answer to apathy and resistance was to use the iron fist, and it never occurred to the crown to replace this heavy-handed technique with attempts to encourage local initiative and industry. Assyria's view of the economy of the empire was simplistic: the ruled territories were there to supply the central state with as much wealth and labour as could be squeezed out of them, and no thought was given to long-range schemes and profits. Here lies one of the basic flaws in the Assyrian imperial structure, a flaw which would reappear in subsequent empires formed after the Assyrian model.

In "The Cambridge Ancient History", second edition, volume III, part 2, edited by John Boardman, Cambridge University Press,UK, 1991, excerpts pp.212-217. Adapted and illustrated to be posted by Leopoldo Costa.

ugly

ReplyDeletesorry that was alyssa

ReplyDeletealyssa is my friend sorry... she told me to say that

ReplyDeletealyssa just yelled at me

ReplyDeleteIt is a great article! It helped me to know better how a situation of taxation in Ancient Mesopotamia looked like. It is very interesting but as i was making a research about this topic amount of information was insuficient. Thanks to Your work i finally got to know better about economical situation in Assyria. I also recommend You this post on reddit: https://www.reddit.com/r/AskHistorians/comments/4mmwxe/how_did_the_neoassyrian_empire_collect_its_tax/. Good luck in Your work and life!

ReplyDelete